27 Jun Sancta Susanna

SANCTA SUSANNA by Paul Hindemith

Teatro Alighieri di Ravenna

One-act opera op. 21, text by August Stramm

Susanna

Csilla Boross

Klementia

Brigitte Pinter

The old nun

Annette Jahns

A maid

Anahì Traversi

A servant

Igor Horvat

First apparition

Catherine Pantigny

Second apparition (child)

Virginia Barbanti

Conductor

Riccardo Muti

Director

Chiara Muti

Set design

Leonardo Scarpa

Costumes

Alessandro Lai

Lighting

Vincent Longuemare

Assistant director

Maddalena Maggi

Stage director

Giordano Punturo

Stage manager

Elisa Cerri

Assistant conductor

Davide Cavalli

Supertitles conductor

Marcello Mancini

Head tailor

Anna Tondini

Tailor

Marta Benini

Head hairdresser

Denia Donati

Head makeup

Mariangela Righetti

Scenography and props

Scene Workshop of Leonardo and Marco Scarpa, Toscanella (Bo)

Costumes and shoes

Tailoring Workshop of the Rome Opera Theatre

LUIGI CHERUBINI YOUTH ORCHESTRA

Melodi Cantores

Choir Master Elena Sartori

Directorial Notes

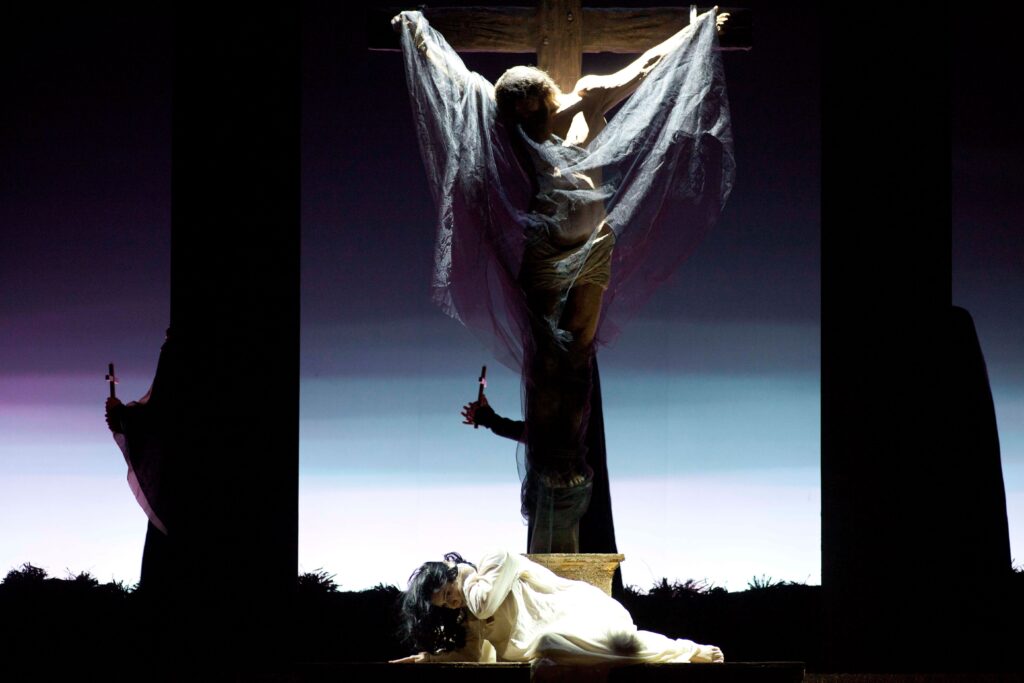

Judgment, freedom, and forgiveness: these are the words that, for me, capture the essence of this opera. The search for freedom that translates into the impossibility of repressing nature, and the necessity of forgiveness. That forgiveness Susanna pleads for, confessing her human weakness, which her fellow sisters deny her, thus failing Christ’s teaching…

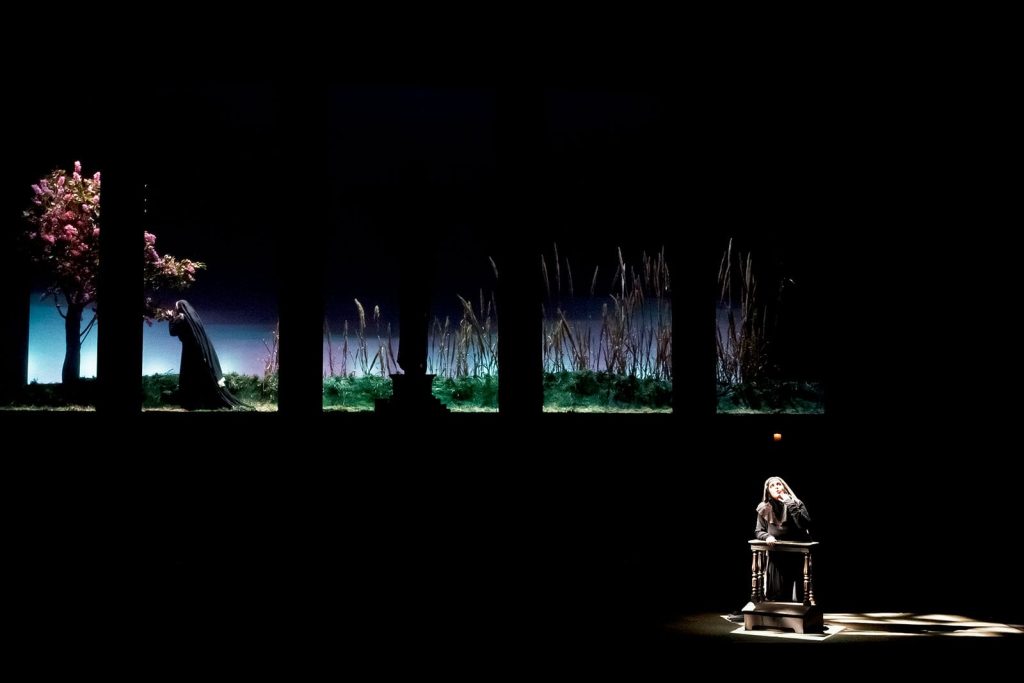

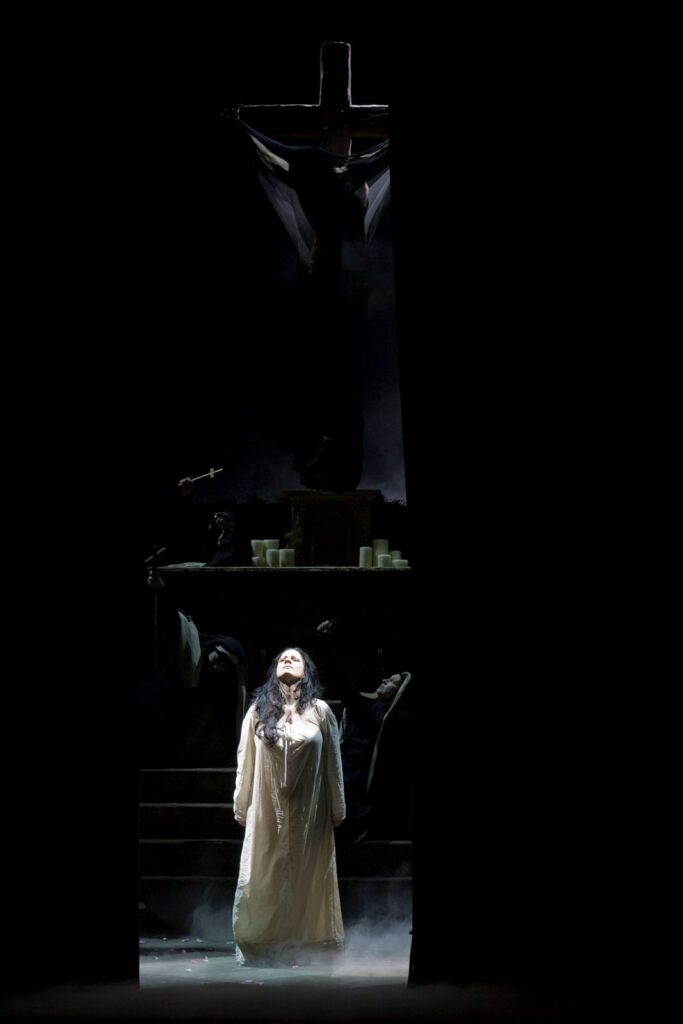

Let us imagine life in the convent… Susanna is young, she is beautiful. She lives her faith with passion: the intensity with which she fasts, prays, and meditates sets her apart

from the other sisters. And with the same intensity, she lets herself be overwhelmed by the awakening of her senses, by the impulses of her young body: like all great figures in history, she does not know the obviousness of everyday life, every gesture of hers is pushed to the extreme.

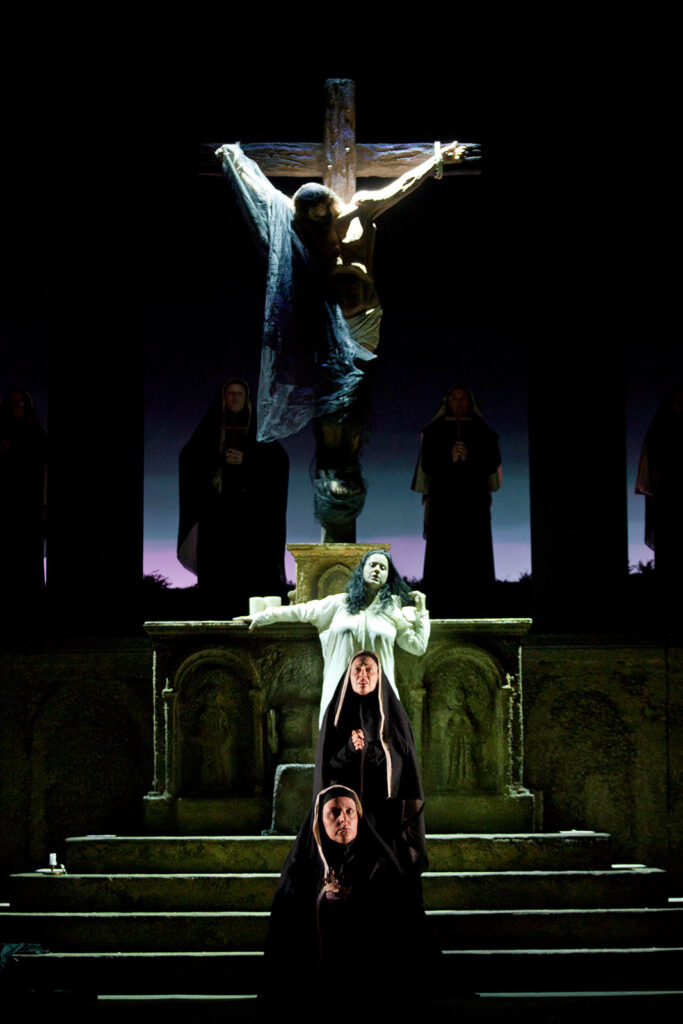

It is in the long dialogue with Clementia that we grasp her strength and her “difference”: Clementia is the one who lacks courage, who lives off the lives of others, who would have wanted to but never dared.

She represents the mediocre pettiness of convention that condemns anyone who dares to rise above it… It is no surprise that it is Clementia who pushes Susanna to the ultimate act, recalling the ancient sin of Beata, and her suffering which still seeps from the convent walls… so many innocents buried among those stones…

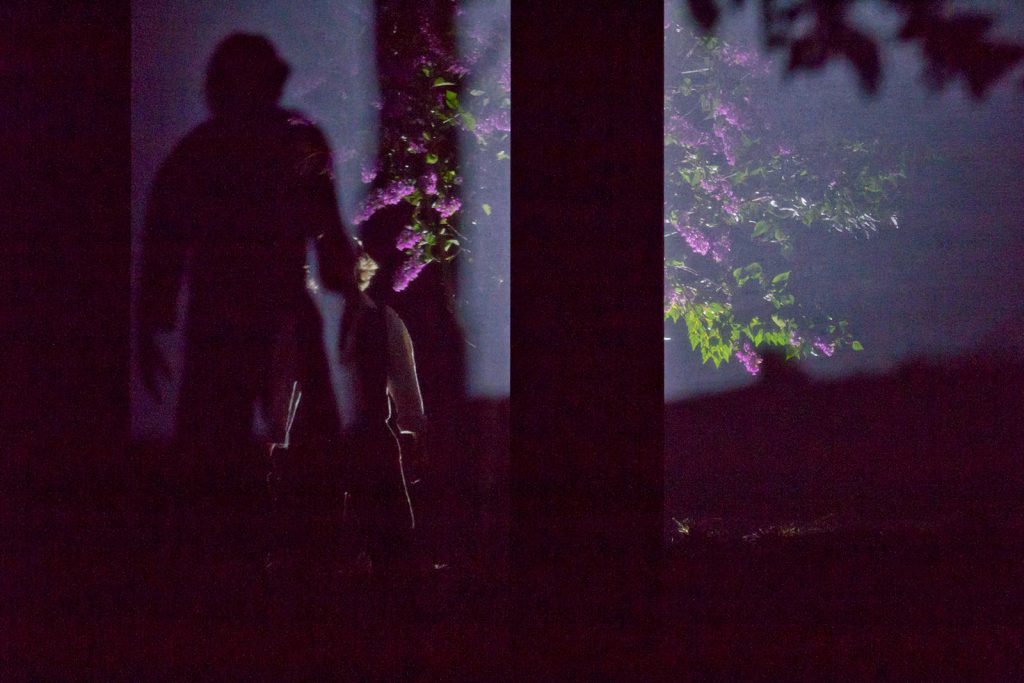

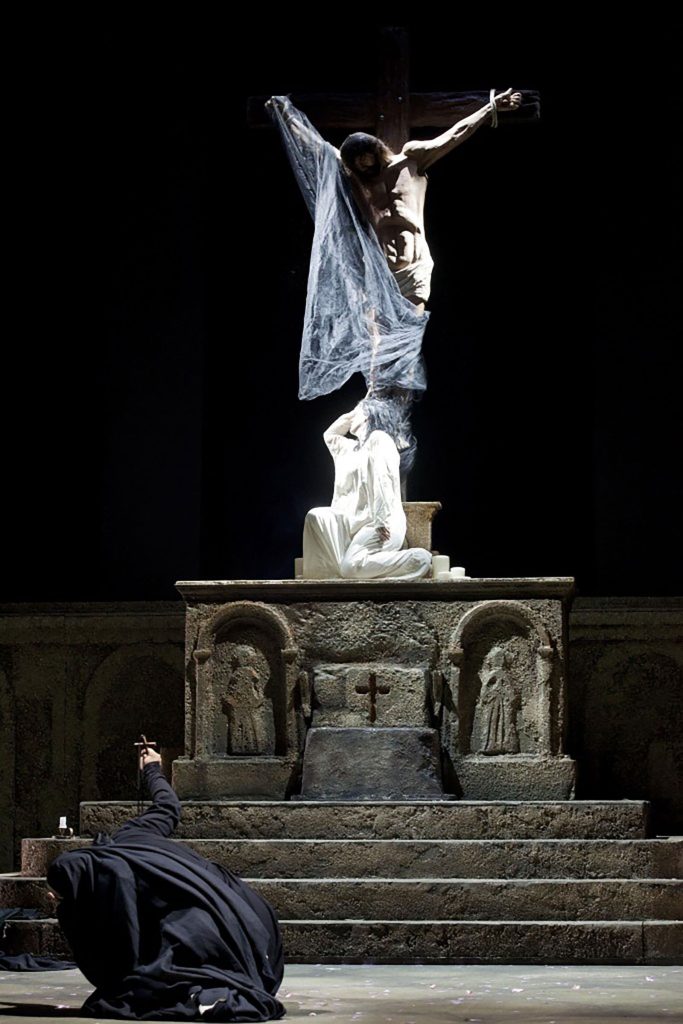

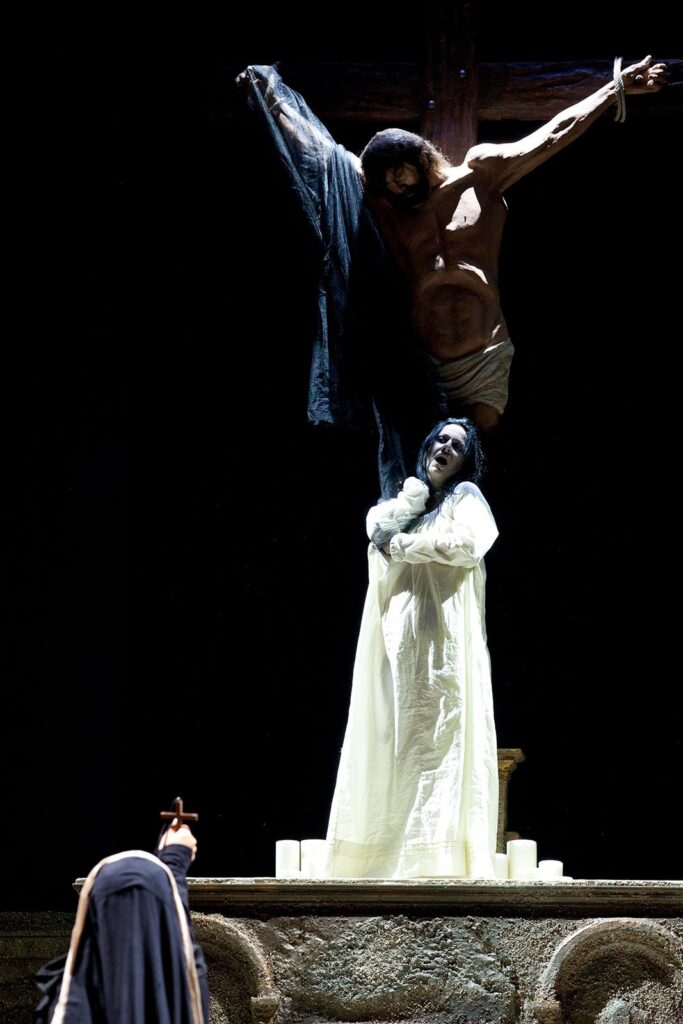

In Hindemith’s composition, sublimated by Stramm’s libretto, there is so much theatrical force and tension… You only have to let yourself be guided… temptation, impulse, hallucination, vibration… it’s all there in the music; within it lies the secret meaning of the stage action and the narrative. It is through the music that the garden, with its tempting smells and colors, infiltrates the convent at dawn, that spring garden embodied by the presence of the maid, in her simple, candid, and “natural” way, capable of striking Susanna, undermining the certainty of her knowledge, and dragging her into the abyss of desire. And it is again in the music, in the excited crescendo of an intense progression, that we read in the finale her desperate plea for help and forgiveness. Then we reach the noble humility with which, faced with the blind and inhuman refusal to understand from the other sisters, she chooses her own fate, removing herself from the judgment of those without mercy.

Thus, before the cross around which the human drama unfolds and which nothing and no one can deface, the fierce cry “Satan!” hurled against Susanna turns back on the sisters, crushing them into dust, while she, “sancta,” finds the light of redemption…

Because it is not given to men to judge…