29 Jun Manon Lescaut

Credits

Teatro dell’Opera di Roma

Teatro Costanzi

Lyric drama in four acts

Libretto by Domenico Oliva, Giulio Ricordi, Luigi Illiaca e Marco Praga Tate

Based on the novel by Prévost

Music by Giacomo Puccini

Conductor Riccardo Muti

Stage Director Chiara Muti

Manon Lescaut Anna Netrebko, Serena Farnocchia

Lescaut Giorgio Caoduro, Francesco Landolfi

Chevalier Renato Des Grieux Yusif Eyvazov

Geronte de Ravoir Carlo Lepore§

Edmondo Alessandro Liberatore

The Innkeeper Stefano Meo

A Musician Roxana Constantinescu

The Dancing Master Andrea Giovannini

The Lamplighter Giorgio Trucco

Sergeant of the Archers Gianfranco Montresor

Naval Commander Paolo Battaglia

Chorus Master Roberto Gabbiani

Set Design Carlo Centolavigna

Costume Design Alessandro Lai

Lighting Design Vincent Longuemare

Orchestra and Chorus of the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma

Conversation with Chiara Muti

by Leonetta Bentivoglio

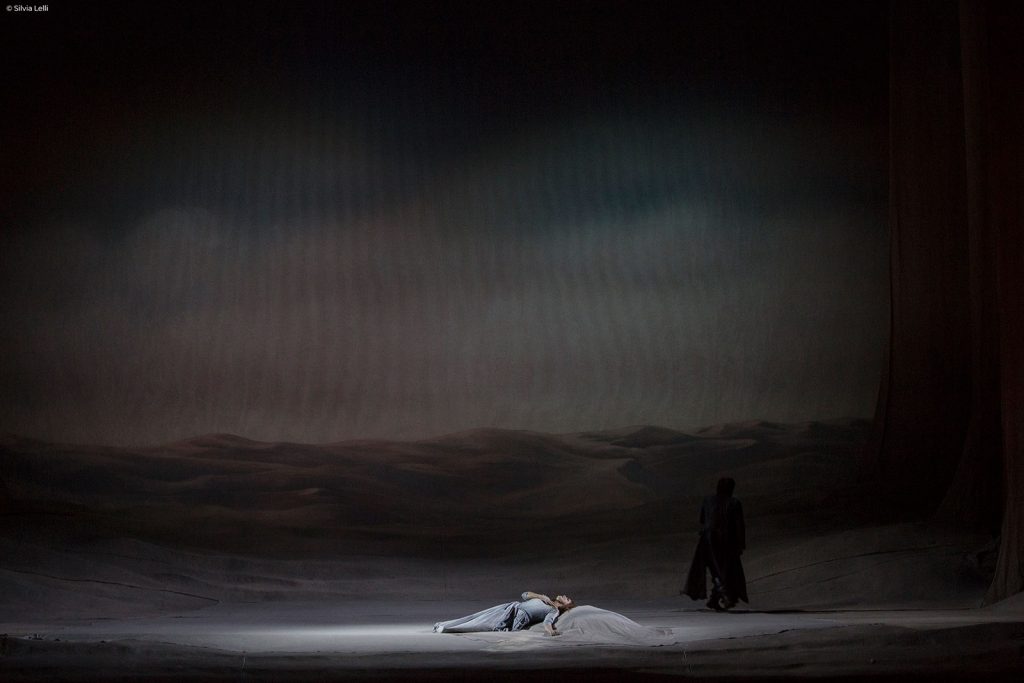

Perhaps one could define it as a great, desperate love dream floating amid the sands of the desert — the staging that Chiara Muti, now in her fourth operatic direction (following Sancta Susanna by Hindemith in Ravenna, Dido and Aeneas by Purcell at the Terme di Caracalla, and Orfeo ed Euridice by Gluck in Montpellier), dedicates to Puccini’s Manon Lescaut.

Premiered in 1893 and inspired by an 18th-century novel by Abbé Prévost (The Story of the Chevalier Des Grieux and Manon Lescaut), this is the first opera in which Puccini fully develops the defining traits of one of his famous, impassioned, and tragic female characters, destined to final sacrifice onstage and to immense popularity with audiences worldwide. Here, the heroine’s fate concludes in the desolate outskirts of New Orleans, where Manon and her beloved Des Grieux pause, exhausted after fleeing the penitentiary.

“Symbolically, that wasteland is also the desert of the soul, through which Manon aspires to freedom, and yet where she finds herself imprisoned,” explains Chiara Muti.

“In seeking a kind of emancipation, Manon arrives at a place of abandonment, solitude, and disorientation, a place she has always inhabited within herself. And to a minuet’s rhythm, Manon breathes her last in the desert that has long accompanied her, steeped in the memories of her lover… ‘Oblivion shall sweep away my sins, but my love will never die.’ Oblivion swallows her small sins, but the great love she inspired renders her an eternal feminine ideal. She’s an unreachable woman — passionate, sensitive, cheerful, perhaps frivolous. But it is her tragic destiny that makes her a timeless symbol.”

Is that why you chose the desert as the leitmotif for your staging?

“Yes. It’s an environment that binds the events together, just as the music weaves in the recurring cycle of the same theme. Past, present, and future merge into a single scenographic space, symbolizing an inescapable fate, already marked from the beginning. Formed by sand — a fine, fragile material — it represents the frailty and precariousness of human life. Moreover, the desert can serve as a metaphor for time: suspended and infinite, like the characters in Prévost’s novel.”

Time means memory…

“Exactly. In the production, the entire story is recalled as a long flashback by Des Grieux, who narrates the events after they have already passed, recounting the journey of the woman buried in the sand. The narrative’s thread is a book from which the ghosts of memory emerge. Each time Des Grieux turns a page, the events he shared with Manon reawaken in him. And as the recollection progresses, the scenes materialize onstage — the inn where the fateful meeting ignites Des Grieux’s love, Geronte’s mansion, the port, the American desert… The various settings are visions of the 18th century, the novel’s era, yet reimagined through the slightly decadent gaze of the 19th century, Puccini’s own time. It’s as if the sand creates mnemonic mirages, resurrecting phantoms.”

So, Manon rises from the past in Des Grieux’s mind?

“Yes. The landscape they inhabit also contains the memory of Manon’s final image, consumed by the desert that has always haunted her, as foreshadowed in the opera’s seemingly cheerful opening, already crossed by something ominous, hinting at the shadow of what’s to come. Even in her vagueness and unconsciousness, Manon senses within her the seeds of a brief, unhappy existence. Before dying, she explicitly acknowledges the desert within herself: ‘I, the deserted woman… in the deep desert I fall,’ she sings in that place of solitude and death.”

The production doesn’t include any modern updates to the libretto?

“No, because the characters in this opera are inseparable from the era that mythologized them. If you modernize them, you risk aging them instead, precisely because they were prophetic when they first appeared — ahead of their time, revolutionary. If, for example, Manon were placed in our age, she would seem like a foolish, frivolous opportunist. But within her historical moment, she takes on an entirely different meaning.”

What kind of meaning?

“In those times, women of every social class had to find a way to exploit their femininity to survive or rise in status. Manon seeks her own freedom by breaking conventions. She lets instinct guide her without asking questions, like a child. Only at the end, faced with the awareness of her inner desert, does she recognize her own superficiality. She never renounces anything — neither love nor wealth. She knows how to exploit Geronte’s riches but also wants Des Grieux’s love. She demands everything, with innocence. She uses every means to free herself from social norms.

But she isn’t strategic, and that makes her original. The great courtesans of that era were utterly cynical: they never made a misstep. Manon, by contrast, isn’t calculating.

She lives lightly and loses everything for love. Passion overwhelms her, to the point of annihilation.”

Is there a difference between Prévost’s Manon and Puccini’s?

“Yes. Prévost — a favorite of De Sade, unsurprisingly — portrays her as an immoral woman, sent to a convent as a young girl by her father, who had recognized her libertine tendencies. She’s a much ‘sharper’ Manon than Puccini’s, who renders her more sympathetic and less amoral. In Puccini’s opera, Manon has no parents, and her brother exploits her, making her a victim.”

Does Manon resemble any other great theatrical figure?

“In Prévost’s novel, Manon reminds me of Don Giovanni, with her obsessive craving for possession and her conviction of being right to seek her own pleasure and gain. By giving herself, she settles the score with love, and it hardly matters if she causes others pain or humiliation. What counts is taking the most from everyone and defying fate with impunity. In Manon, using her body to obtain what she desires makes her even more negatively judged than Don Giovanni, who — being a man — is treated more favorably as a seduction philosopher. It’s interesting how the woman chasing Don Giovanni, Donna Elvira, seems to us a hysterical, masochistic madwoman, while a betrayed man like Des Grieux appears not weak, but as a lover of profound virtues.

Manon is seen as frivolous, undeserving of Des Grieux. And while Don Giovanni is an explorer of emotions, Donna Elvira is merely a fool. For men and women, history has always applied two separate standards.”