03 Jul Guillaume Tell

Directorial Notes

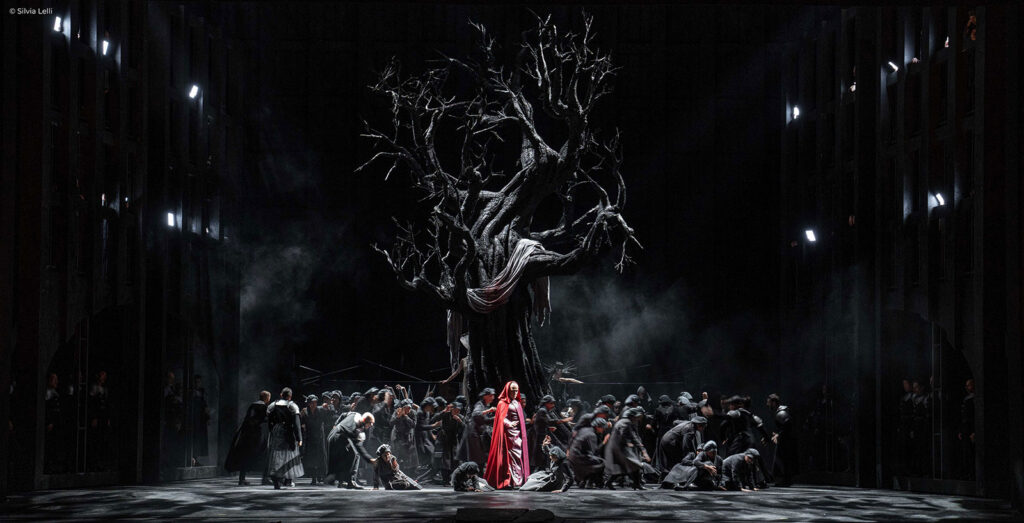

At the beginning, everything is darkness.

A labyrinth of walls rises all around, suffocating the horizon.

Squared, aseptic buildings sketch a city inspired by the visionary Metropolis by Fritz Lang, the 1927 cult film that prophetically depicts the annihilation of society and humanity, automated and enslaved to profit.

Man has imprisoned himself by erecting walls of screens that blind the sun.

Once the mist has dissipated, we find ourselves facing a multitude of prostrate beings, their gaze submissive, their eyes fixed and blinded by cold, distorted lights of a chimera, imprisoned by the reflection of an image that, like Narcissus’s smile, leads to the suffocating abyss of a hypnotic limbo where numbers are worth more than content.

Walking automatons in a nonsensical and illegible flow of time.

Guinea pigs searching for fleeting rewards, virtually chained, their judgment formatted to the tyranny of a single, dominating thought.

Memories are lost, the past has nothing left to teach, we pass down nothing but the present moment, relegating ourselves to oblivion in the passing of time.

Immersed in mist, the memories of who we were lie on the ground, dusted over, eroded by forgetfulness, ready to be recycled: fairy tale books, childhood stories, dolls, kites, ships… the children, symbols of rebirth, still search through that pile of refuse, as if sensing a call to a precious past that would define them.

Time-worn, a crossbow resurfaces from the ashes.

A worthy son of an archer, Jemmy raises it proudly and runs to his father.

The son has recognized in that object a divine sign of destiny. His father is Guillaume Tell.

The crossbow then becomes the sacred symbol of the transmission between generations.

In a single gesture, the story finds its highest meaning!

In a reciprocal exchange, father and son metaphorically arm themselves with a consciousness that celebrates humanity in its highest values.

To the orphans of answers, the future foretells the blind slavery of ignorance!

Guillaume is “the Archer and Savior” sung about in Schiller’s final drama in 1804. An ancient legend credits Tell with having led, in the early 14th century, the Swiss Confederation to independence from the Habsburgs. In this fight of the oppressed against the oppressor, virtue, dignity, and humanity are the weapons with which the Romantic poet defeats evil.

The legend has universal significance! Guillaume is, in my view, an Archer and Savior in a biblical sense.

In one of the illustrations from John Milton’s masterful poetic fresco Paradise Lost (1667), the painter William Blake captures and sublimates the moment when the Archangel Michael, bow drawn in hand, hurls the devil and with him all the forces of evil into hell. It seemed to me to be the very image of Tell!

Guillaume is humble, pure, incorruptible to vice!

The devotion he has for his land is tied to his boundless love for the nature that overshadows it. We are intentionally orphans on stage.

The Alps, waterfalls, forests, lakes, streams, all the elements resonate in him and comply with his will in a pact of mutual respect. The waters, the winds, and the storms, in an alliance of purpose, follow the deeds of humanity, contemplative and mystical, the “Noble Savage”.

A hero, reluctantly, more for moral virtue than political choice! Not a warrior but a just man!

At the beginning of the opera, the conflict between the incorruptible and the corrupt reveals itself!

In a desolate atmosphere, Ruodi, a number among numbers, rises from the dust and sings a song of idyllic abandonment to fate… “Accours dans ma nacelle… du plaisir qui t’appelle c’est ici le séjour…” An irresponsible call to forgetfulness…

The “nacelle” that the soul fisherman speaks of is the floating cradle of a peaceful and guilty social sleepwalking to which the inhabitants of the land echo, as if enchanted by the song of the sirens, in an opaque acceptance of enslavement.

Guillaume responds: “Il chante en son ivresse… de l’ennui qui m’oppresse il n’est pas tourmenté. Quel fardeau que la vie! Pour nous plus de Patrie! Il chante, et l’Helvétie pleure sa liberté”.

The Helvétie of which Tell speaks with supreme and desolate pain is the oppressed humanity that cries for its freedom!

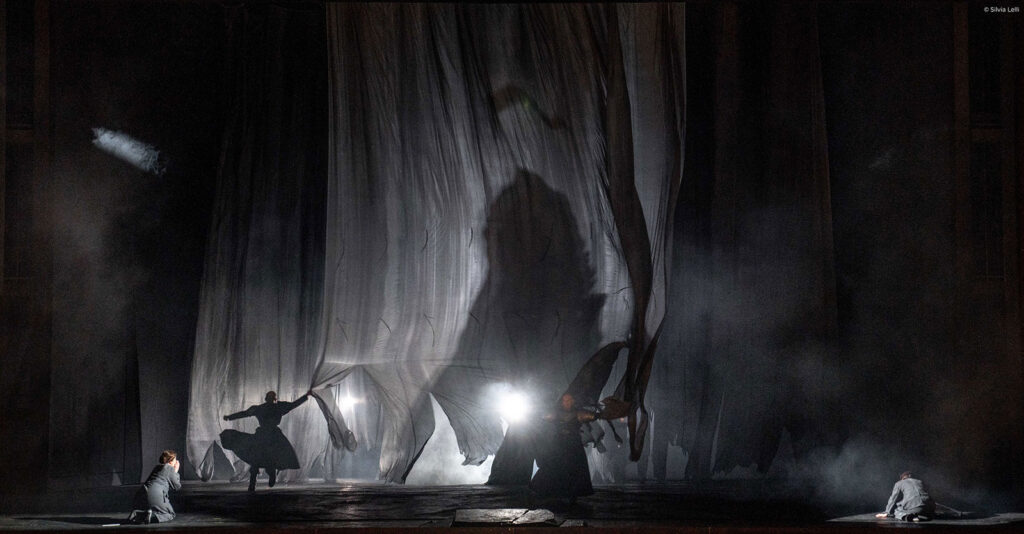

Thus, water, air, earth, and fire, the four elements, ancient creations of man, will appear throughout the opera on the walls of labyrinthine rotating prisons, symbolizing a nature. trained to chase changing moods, fill voids, and fulfill gazes.

The oppressed humanity continues to celebrate, and Guillaume thunders all his indignation: “Un peuple sans vertus n’enfante plus de braves… que légueriez-vous à vos fils? Les fers dont vos bras sont meurtris…” That is, Tell reminds us, in his marvelous tirade, that the source of our ancestors ” noble blood is now dry… that a people devoid of virtue no longer generates heroes and that we will leave our children the chains we ourselves drag…”.

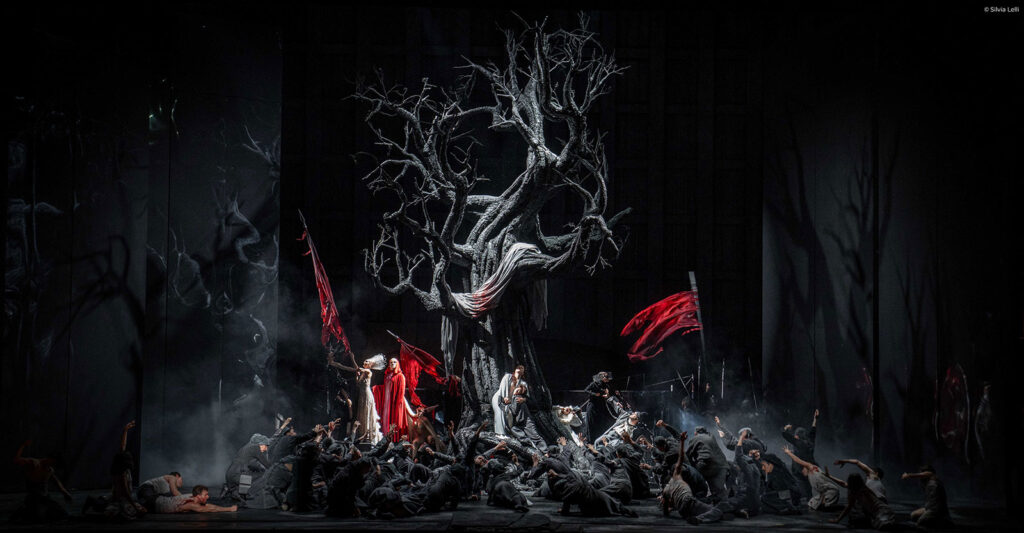

At the “Fête des Pasteurs,” celebrating a triple wedding, in an apparent state of calm, the three brides, having received the blessing from the elder Melcthal, symbol of ancient wisdom, will end up violated and metaphorically devoured by the henchmen of evil, in the general indifference of the onlookers. Nothing anymore can shake consciences… Thus, when Leuthold bursts onto the scene, covered in the blood of those who dared to lay hands on the innocence of a daughter, he will find a wall of pitiless shoulders, cowardly turned to meet him. Tell, hearing the groans of the outrage suffered, rushes forward and, looking with contempt at the passive multitude, without hesitation, guided by a moral duty, takes it upon himself, sacrificing himself, for the salvation of others! The exemplary courage rekindles a spark of hope… and in a cry of resistance against evil, the first act closes.

Evil is personified by the merciless figure of Gessler, no longer a governor at the service of the Habsburgs but the embodiment of the devil. Around him reign the seven deadly sins: Wrath, Greed, Envy, Gluttony, Sloth, Lust, and Pride, the worst of all.

They triumph unperturbed, accomplices in the darkness of despair. From time to time, at the sound of a horn, a flash of light appears as a reminder of a nature ready to embrace us and remove the black veil of blindness from our eyes.

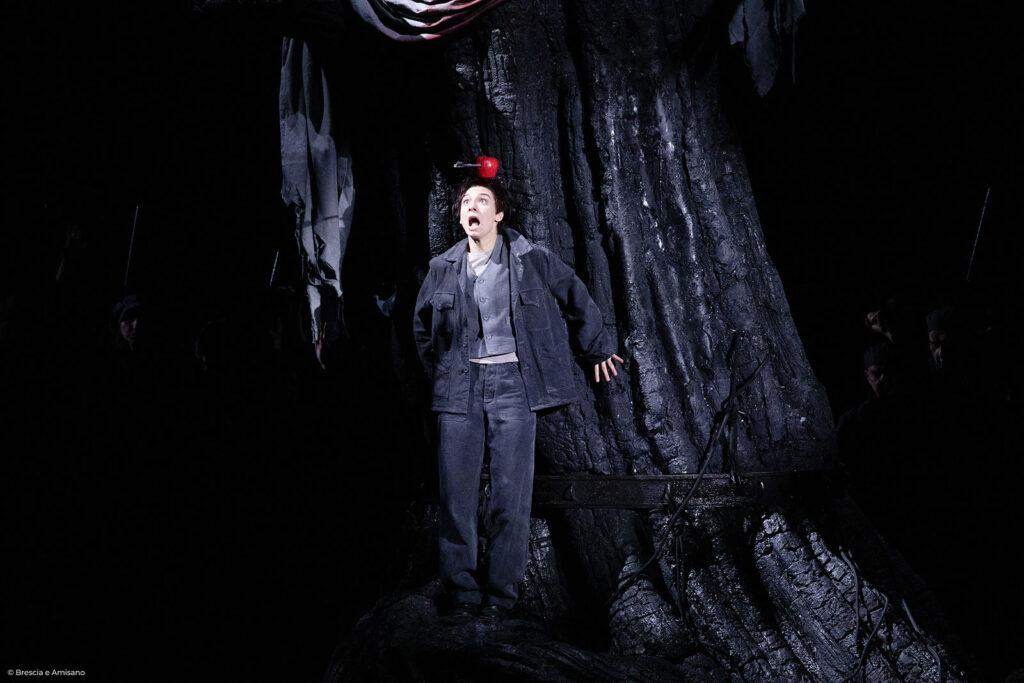

In a world devoid of color, the red of Gessler’s robe is biblically characteristic. Red like the robe, red like the plume, here a bloodstained shroud raised on the now withered tree of knowledge, to which one must bow irrationally, and red like the apple of free will, which man plucked from God, tricked by the devil, in the bliss of Eden. The tempting serpent knew how to tickle man’s presumption and vanity, giving him pain and dust. Thus, the hunting scene at the beginning of the second act transforms into an inhumane and cynical massacre! The hunters are nothing more than an emulation of evil. Man goes hunting for man and, by not recognizing himself, denies his humanity!

“Le cri du chamois mourant se mêle au bruit du torrent. L’entendre exhaler sa vie estil un plaisir plus grand?”.

The pleasure of intoxication by the last breath of a prey that no longer recognizes itself as human transforms into the game of massacre of a mother and her children. But a noise disturbs the inhumans…

The village bell calls for a metaphorical return to oneself… “Du village la cloche sonne, c’est notre retour qu’elle ordonne…”.

Then a father will lift the lifeless body of his son, in a restrained cry of violated pity, while, in the distance, the echo of a choir will softly sing: “Voici la nuit…” “Here is the night”, as if, amidst flashes of stars, Angels, with a rustle of wings, receive the souls of the innocent to the heavens.

The great scene of the third act is an anthem to presumptuous Babylon, which confuses the languages of men, spreading chaos, disorder, and death. The ancient tree of knowledge, a martyr of man’s abuses, rises, twisted, as a representation of nature outraged, hostile to man. Next to the tree, the ancient serpent waits… at his feet, all around, the poisonous apples of sin lie on the ground, ready for consumption. Gessler imposes upon men the need to prostrate before injustice, offering the deadly capital sins in a whirling dance of abuses and humiliations. The diktat of bowing to the plume, raised in the public square of Altorf, is the symbol of the absurdity of the rules to which future generations will be subjected. We bow to stupidity, with the swollen pride of feeling free!

In this atmosphere of decay, Tell, the pure one, is called to commit an act against Nature! That same Nature that respects him and from which he draws the sense of what is right! The father is forced, by a whim of the devil, to arm himself and shoot at his son! That son, by nature, must be able to survive him! The devil challenges the Lord, tempting His favored creature! Guillaume urges his son to invoke God, looking to the heavens: “Invoque Dieu, c’est lui seul, mon enfant qui dans le fils peut épargner le père!” Never was a scene more mystical! The allegory of Tell’s gesture, with the ancient crossbow, is called upon to strike the apple, the burning symbol of man’s betrayal of God, placed on the pure forehead of that son sacrificed to the tree of knowledge, as if he himself were the fruit of original sin! For the devil, the sins of the fathers fall upon the children, and Gessler made this clear to Tell when he replied with contempt to the question about the son’s crime: “Ca Naissance” “His birth!” But pride, that sin of Hybris that the Ancient Greeks so demonized, has not soiled Tell’s purity!

And, having fired the arrow, innocence is preserved! The child exults: “Ma vie est conservée, mon père pouvait immoler son enfant?” With this gesture, Tell redeems all of humanity, reclaiming the ideals of Divine Justice! Gessler writhes in displeasure, and, unsatisfied, chains Guillaume, foreseeing for him eternal suffering and dark imprisonment among the serpents.

But the forgotten Nature awaits its moment! The storm of the fourth act is a metaphor for an inner battle. In this struggle, two shadows face off: good and evil, the human and the inhuman. Guillaume seems to fight against himself, the fragility of substance, the doubt that seizes, even for a moment, the soul of every hero! But the fury of the elements, once again, spares Tell, consecrating him as “Enfant de la nature”. Jemmy then hands the crossbow to his father, who, armed with the awareness of what is right, shoots the arrow into the heart of the oppressor. Gessler plunges into the abyss, and with him, the walls erected to deceive us. Amidst smoke and fire, the second Dantesque death, metaphorically resulting from Tell’s second arrow, rises, impassive, as a warning to the living.

Then, a new light emerges from the ruins. Humanity, rediscovered, seems to look inward and feel itself for the first time. A multitude of souls advances, holding their breath in ecstasy, as if it were a sacred rite, and, shedding the weight of the dust’s weariness, humble, no longer humiliated, and clothed in a new beginning, stretches its arms to the heavens, intoxicated and moved by the beauty of creation. The immense, miraculous Rossinian finale is an anthem to the reconciliation with Nature! It seems to echo the verses of Schiller’s Ode to Joy: “Do you sense your Creator, world? Seek Him above the starry sky, above the stars, He must dwell”.

The poet urges us to contemplate the creation as the only source from which to draw to echo in us the mystery of superhuman answers. And here, then, Nature, in all its overwhelming beauty, appears, not virtually but intentionally, painted on a canvas by the skilled hands of artists passing on the secrets of an ancient theater, whose participants resist the annihilation of thought. A theater that has always spoken of man to man! A temple of humanity whose cathartic benefits remain unchanged since Homer’s time. A theater whose charm purifies thoughts and dresses the gazes of children’s innocence. Once the curtain is raised, a dream speaks to us and moves us still, as it did a thousand and a thousand years ago… In front of this apotheosis of freedom, understood in its deepest sense, Rossini set down his pen… seized by a tremor of eternity. As with Schiller, Guillaume Tell would remain the last of his works. “The Archer Savior” pierced them both, or perhaps, by filling their creativity, he has perpetuated their immortality. Rossini cannot venture further. The comedy is finished, and he seemed to hear echoing in the air the grandiose verses of the last song of a paradise lost and found: “A l’alta fantasia qui mancò possa; Ma già volgeva il mio disio. e’l velle, sì come rota ch’igualmente é mossa, L’amor che move il sole e l’altre stelle”.

Chiara Muti