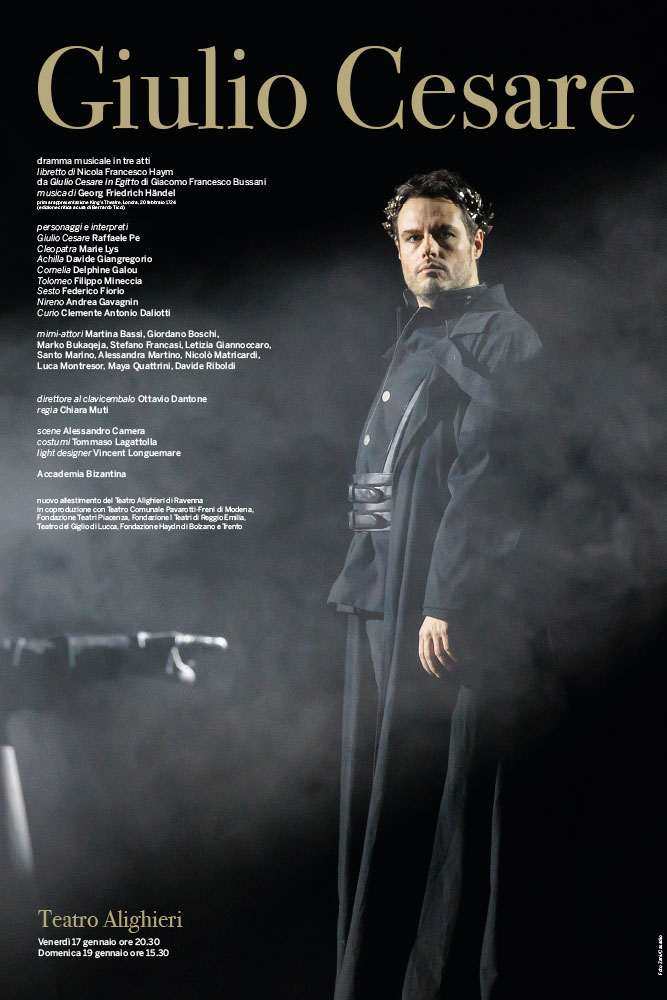

04 Jul Giulio Cesare

Director’s Notes

“What could there be in that ‘Caesar’? Why should his name resonate more than yours?” Shakespeare.

What makes a man immortal? The greatness of his destiny.

Giulio Cesare has entered legend, and yet he was a man like any other… like all of us, he had a time to leave an indelible mark on the earth.

His deeds have become history, and history, passed down, has made him immortal.

It should therefore not surprise us that, among the many artists who have wanted to celebrate him, including poets and painters, playwrights and sculptors, a composer of Handel’s stature, another survivor of oblivion, undertook the demanding task of setting the myth of the man who, more than anyone else, made Rome legendary to music.

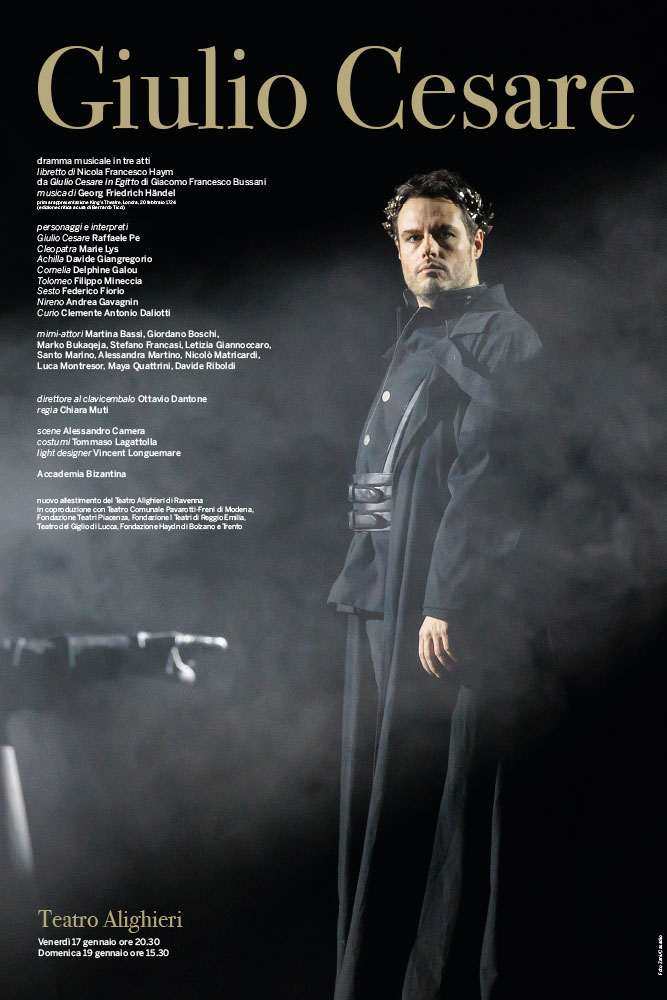

The premiere of Giulio Cesare took place on February 20, 1724, at the King’s Theatre

Haymarket in London, under the patronage of King George I of England, founder of the “Royal Academy of Music”, directed by Handel.

But what does Baroque opera have in common with the political and military genius of Caesar? I would say nothing! And the Italian libretto by Nicola Francesco Haym is proof of this.

The poet reduces the plot to a succession of numbers, evenly divided among the singers, encoding the moods of the characters and imprisoning them, according to the codes of the time, in the rigid “da capo aria” format, composed of two stanzas, the first of which is repeated at the end with variations and embellishments intended to highlight the vocal and virtuoso qualities of the stars of the time.

This mechanism damages the theatrical action in favor of vocal feats, which, especially in the so-called show numbers, drove the audience crazy!

The English audience, accustomed to the great Shakespearean theater of action and words, which for over a century had been able to admire the classical tragedy The Life and Death of Julius Caesar, inspired by Plutarch’s Lives, a detailed and powerful psychological analysis of the fall of great men when they presume too much, certainly did not go to the opera to reflect!

But what remains of the theater? And what, concretely, must the director do? Well, the answer is all in the musical genius of the composer: George Frederic Handel.

When one is faced with such substantial material, one might also say that words do not. matter, and one can rely on the music to give a deep meaning to our directorial vision.

Handel is a poet! Exciting and engaging, moving and exhilarating!

Thanks to the intensity of his vocal lines and the chromatic dynamism of his orchestra, he redeems the static nature of the action and enriches the characters with meaning. By digging into the human condition and revealing the complexity of contrasts, he gives us moments of such emotional tension that we can say he has reached, through music, the heights that Shakespeare touched with words.

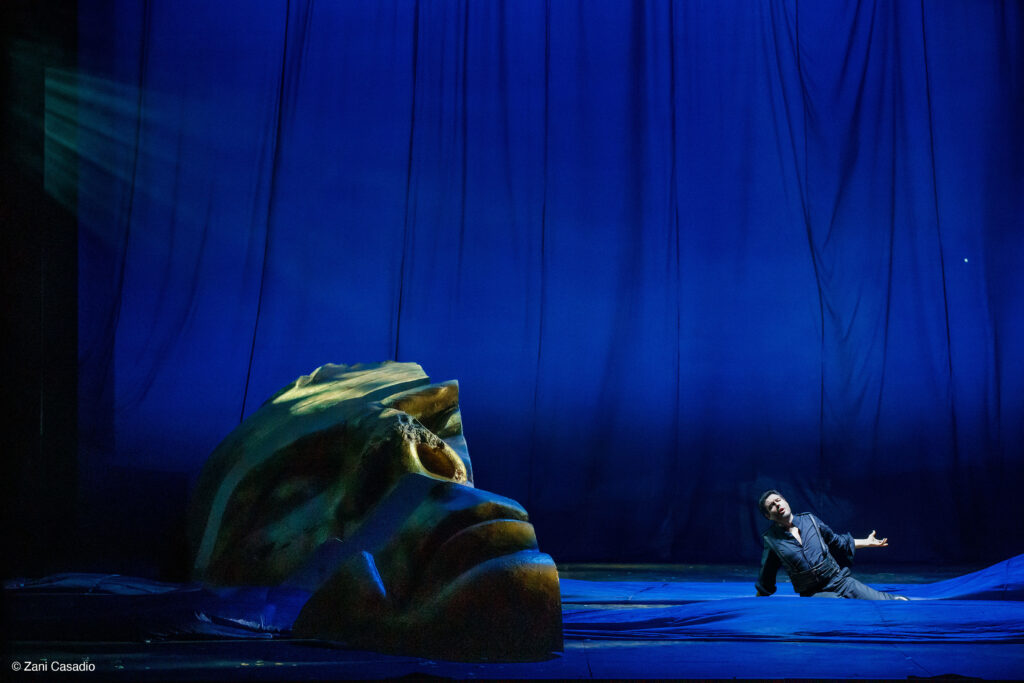

The direction, reinforced by the melody, therefore bends to the symbolic and evocative dimension! The scene opens onto a metaphysical space, whose colors metaphorically recall the gold of the sands of Egypt and precious metals, as well as the enigmatic faces of the pharaohs’ masks. On the horizon, eight fragments rise, between heaven and earth, silent ruins of a world that was, forming a circle that vaguely recalls the mystical site of Stonehenge, whose name means “hanging stones.” Never was a name more suited to a gathering of souls called to earth from the afterlife.

At the foot of the stones lie eight lifeless bodies, mixed with the colors of the sand. In the center, a heap of garments, rags, and ornaments seems to animate and come to life.

The three Moirai, creators of destiny, Roman deities of the Greek Moirai, rise from the heap of rags and draw the bodies to them, animating them, like a birth, with the desire for existence.

Clotho, the spinner of life, Lachesis, the weaver of destiny, and Atropos, the unyielding fate of death. They dwell in the Underworld, indifferent to the fate of men, spinning their destinies, assigning them a place, a space, and a time that clothed them with a new identity.

How much fate determines our destiny and how much is determined for us… is the dilemma that this opening seeks to raise. Our eight newborns immediately understand that the dance is for power. The Moirai raise the laurel to the sky; whoever succeeds in taking it will be master of their fate. But only one will bear its weight.

Caesar rises and crowns himself emperor. The Moirai recognize him as the man who will leave his mark. Thus, he presents himself first to the public with his famous phrase “Cesare came, saw, and conquered”. He who, posthumously, elevated Rome to demiurge, ancestor of Aeneas, descendant of Venus, he who came… and saw beyond time… and conquered death. Yet even he, to gain immortality, needed mortals.

Here then come the others, the anonymous, the submerged of history, the forgotten ones, who move those fragments like pieces on a chessboard, in a dance, often incomprehensible but necessary to history, and who ultimately compose them into the face of one of them, the visionary, the one who, justly or unjustly, guided the events, shaping them in his own image. Eternally dominant, his eyes turned to the sky as a warning to death.

And here, alongside “fate”, a new theme emerges: “Survival”.

“He sits upon the world, tight like a colossus; and we, small men, pass beneath his legs, looking around to find ourselves tombs without honor. There comes a moment when a man is master of his own fate: the fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves, that we are underlings”.

Shakespeare.

Cleopatra without Cesare is no longer Cleopatra… and like her, Cornelia, Ptolemy, Sextus, Achilla, Curio, and Nireno… are nothing but reflections of light. The plot is simple. The historically verified events of Cesare’s arrival in Egypt in 48 BC, fleeing from his rival Pompey, who escaped after the Battle of Pharsalus seeking help, are narrated. Upon his arrival, Cesare finds himself embroiled in another struggle for power, this one between Ptolemy XIII and his sister Cleopatra VII. Now, to gain Cesare’s favor and secure the throne, Ptolemy asks his general Achilla to have Pompey murdered and present his head to the Roman rival. Plutarch recounts that, upon seeing the macabre gift, Cesare wept, and although the emperor briefly mentions it in his commentaries, it is easy to believe that Pompey had been his son-in-law, having married his beloved daughter Julia.

But an opera without love is not an opera, and here comes the poisoned arrow of Eros to disturb the great events of history! The appearance of Cleopatra, barely twenty, astute and sensual, is a bolt from the blue! Cesare is captured and takes her side, and after various plots, trials, and battles, and a swim away from a sinking ship, stripped of armor and weapons, Cesare, the miracle survivor, reorganizes and deposes Ptolemy (who in the opera is killed by Sextus), crowning Cleopatra as the sole queen of Egypt!

The events and characters are true in history, with some historical licenses (among the most obvious, Cornelia is the stepmother, not the mother of Sextus, who did not kill Ptolemy, who would have died in battle drowned in the Nile, and Achilla was betrayed by Cleopatra’s younger sister, Arsinoe IV).

What is certain is that we are far from the tormented and consumed Cesare by power that the English admired in 1599 under the thatched roof of the Globe Theatre in London. The Baroque Cesare, symbol of marble justice and temperance, sung by the castrato Senesino to exalt and honor King George I and the new Hanoverian dynasty in power, is anything but ambiguous and becomes dehumanized to exalt, in the apotheosis of Rome, the virtues of the enlightened monarch.

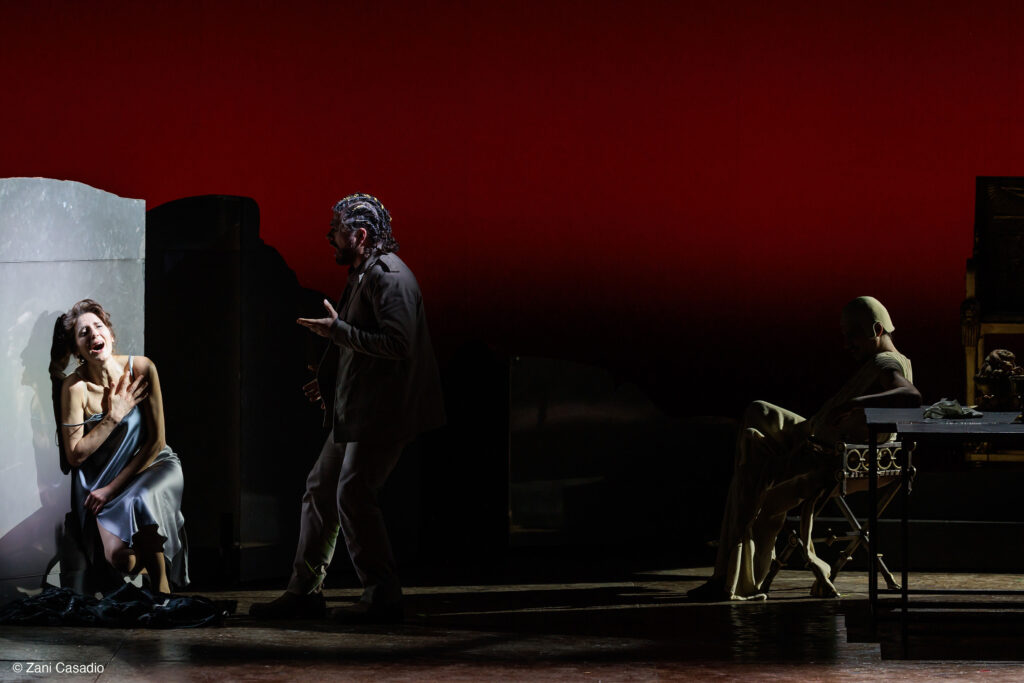

The opera is thus divided into two distinct ethnic groups, in perfect symmetry of timbres and opposing characters. The civilized Roman quartet, dressed in dark clothes recalling the cultured and formal world of the West, and the barbaric Egyptian quartet, whose lascivious and sinuous clothes evoke the splendor and magic of the instinctive East.

Vice and virtue, facing each other like a mirror. In the imagination of 18th-century Europe, the Western civilization that made Rome great, of which the English considered themselves direct descendants, and which knew how to evolve by mastering passions, is contrasted with the disorder of Eastern customs. Good and evil, no longer colonizers and colonized!

The characters have no evolution, except for Cleopatra, who, falling in love with Caesar and aligning herself with the destinies of the West, ascends to the paradise of the righteous. There is nothing in the music that characterizes the different ethnicities!

Each character is animated by a main emotion: Cesare’s greatness and justice, Cleopatra’s dissimulation and seduction, Cornelia’s grief and perseverance, Sextus’ vengeance, Ptolemy’s treachery, Achilla’s desire, Curio and Nireno’s loyalty.

Among the numerous musical peaks of the opera, one in particular moves me: the recitative in which Caesar scatters Pompey’s ashes to the wind. The moment of greatest poetry in the opera, for a moment the words become stones and offer a deep reflection on the fragility of the human condition.

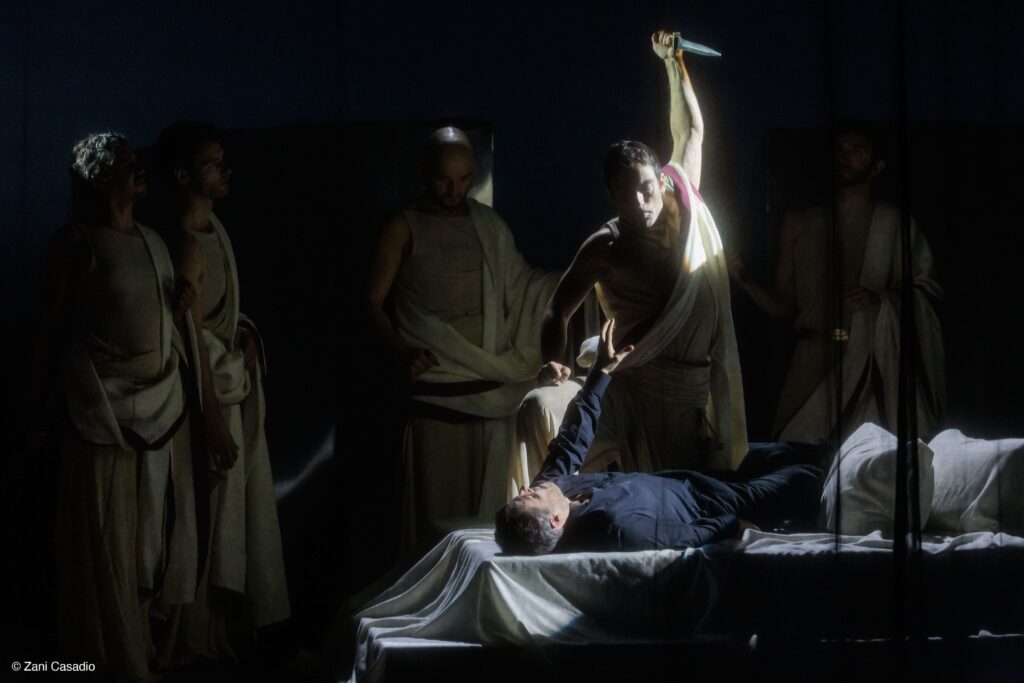

And then, like mirages of what will be, I wanted to anticipate on stage the dark premonitions, the tragic fates of Cesare and Cleopatra. Two of the most iconic deaths in history. He, stabbed in betrayal, in the Senate, under the great statue of Pompey, and she, bitten by an asp, having lost Mark Antony, to escape the humiliation of having to submit to Octavian. Shakespeare fixed these moments of history, transforming them into high poetry, and then new tributes to the Shakespearean world emerge: the appearance of Cleopatra, disguised as Lydia, to charm Cesare, becomes a reference to the fairies and spells of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the mythical scene where Titania, the fairy queen, humiliated by an enchantment from Oberon, falls in love with an ass, as a metaphor for the love that blinds reason, and we are not far from reality, since Cicero himself wrote that the love between Cesare and the Egyptian queen contributed in part to his downfall. For contemporaries, a sorceress capable of bewitching the greatest men of Rome, making them lose awareness of their greatness, to the point that after Cesare and Mark Antony, it is told that Octavian, finding himself in her presence, avoided her gaze for fear of being enchanted!

Another reference concerns Sextus and his inability to find vengeance. This son terrified by the shadow of a father who urges him to act, recalls the enigmatic prince of Denmark, Hamlet, who can do in thoughts what he cannot do in deeds.

A special place must be reserved for the character of Cornelia. A Mater Dolorosa who bears the weight of all the injustices and violences suffered by women throughout the centuries. She nobly rises to defend the flame of passion that she has unknowingly ignited in Achilla and Ptolemy, which will pit them against each other, leading them to ruin.

Ptolemy was fifteen at the time of the events, and his indisputable historical immaturity translates on stage into an unstable and angry character, frustrated and capricious, imagining doctors instead of tutors. His unhealthy relationship with the opposite sex is expressed in a harem where dolls and women metaphorically confuse the objectification of the female body! He engages in an almost incestuous relationship with Cleopatra, a mix of hatred and love, brother and sister, almost a single entity, male and female, spouses, who the father had left in the will to rule the kingdom together.

Kings and queens, they fight on a long golden cloak, symbol of supremacy over Egypt, which, through disputes and turmoil, they will finally tear and divide in two, like the factions that will distinguish them. In the scene on the Nile, a sea of blue silk fills the space with calm waves, whose harmonies anticipate the sweet Mozartean chromatics.

At the close of the opera, at the end of the love duet between Cesare and Cleopatra, all are gathered on stage… alive and dead… around the anonymous fragments transformed into the face of the victor, slow, apathetic, letting fall the useless material that distinguished them, and, casting off the weight of the journey, they return to the limbo of souls, ready to be reanimated for a new destiny.

The last to fade is Cesare. Then the Moirai, taking the laurel from his brow, raise it to the sky, awaiting a new chosen one. In the final, Harmony triumphs, the lights come on, and filled with the best hopes, the spectators of one of the operatic masterpieces of all time are urged to fill their hearts “with joy and pleasure”.

Our time is now… and fate weaves unexpected plots.