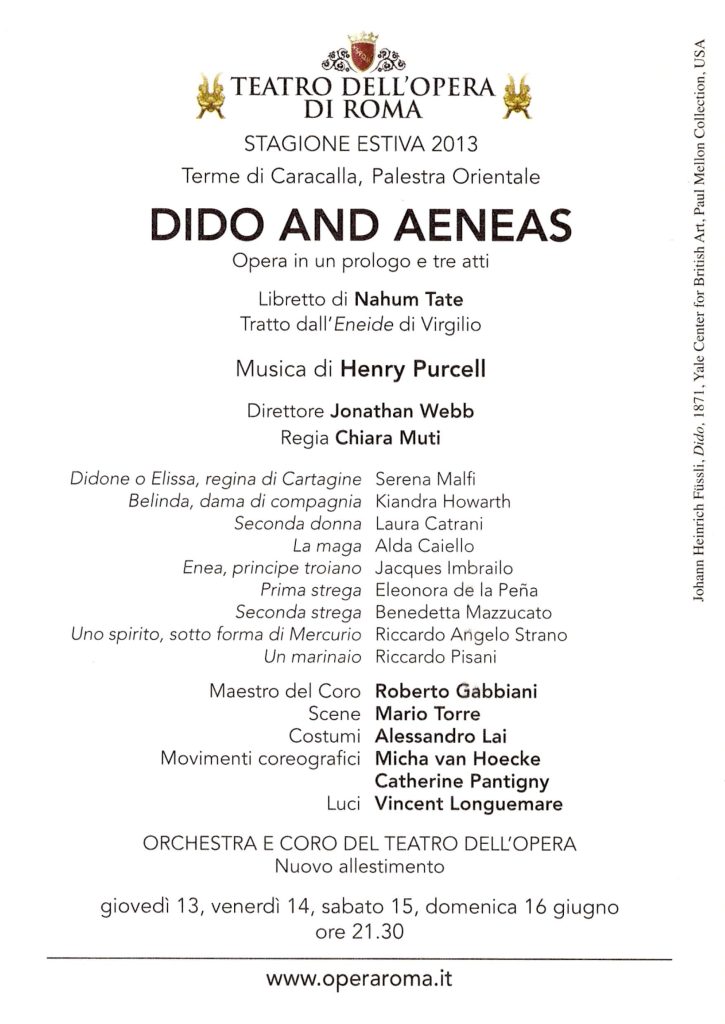

25 Jun Dido and Aeneas

Directorial Notes

DIDO AND AENEAS AMONG THE MATTER OF DREAMS. Interview with Chiara

Muti by Leonetta Bentivoglio

Chiara Muti is an intelligent and sensitive actress who, throughout a career rich in successes, has always made interesting choices both in theater and cinema, pursuing unpredictable roles, adventurous paths, and experiments that have highlighted her multidisciplinary talent and her marked musicality. Her operatic directing debut dates back to last year, with the staging at the Ravenna Festival of a challenging and deeply feminine work like Hindemith’s Sancta Susanna. Chiara Muti approached it with a rigorous sense of music, a thorough work with the performers, and an inventive and poetic interpretation. Now she returns to directing to stage the seventeenth-century opera Dido and Aeneas by the English composer Henry Purcell, in the impressive setting of the Baths of Caracalla.

“An open-air performance terrifies every director,” she confesses, “because it places you in a situation where you cannot fully control the clarity of the lighting. On the other hand, the space of the Palestra Orientale of Caracalla is extraordinarily evocative: you breathe History with a capital H there… So you have to respect it and let the place live on its own, without scenic overlays that disturb its nature.”

What will the setting of your production be, then?

“A simple circular platform represents time turning, just as the hands turn on a clock face. The fast pace of Dido and Aeneas pushed me toward this choice, where events unfold frenetically. From the love of the two protagonists to Dido’s suicide that closes the opera, it’s as if fate encircles the characters with burning rapidity. Time runs driven by fate, which in Purcell is depicted by the witches.”

That is, creatures arriving from malevolent dimensions…

“Malevolent, yes, but also ironic, which is typical of English theater, where fantastic realms are always told with a bent towards the comic. It is laughter that seeps into tragedy, a joking about the downfall of others. There is humor, for example, in the sinister appearances of much Shakespearean theater, tied to an uncontrollable and intangible world of elves, sprites, magicians, and witchcraft. Think of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Tempest. Moreover, since the Caracalla space is completely open, with no entrances or exits, the chorus must always be present as a commenting function, like in Greek theater. So I thought of channeling the various cultural levels that feed the beauty of this work by giving the chorus different faces.”

Which ones?

“At times it seems like a group of seventeenth-century courtiers, ghostly and illuminated by torches. This vision, combined with the ruins of Caracalla, evokes the first English travelers who at the end of the seventeenth century began tourism by visiting the remains of ancient Rome. But the chorus, in different passages, can also become the world of the Greco-Roman mask and that of the comic lazzi of the commedia dell’arte.”

Earlier you mentioned the cultures converging in this opera. What did you mean?

“Purcell, in Dido and Aeneas, succeeded in blending certain characteristics of Italian lyricism (you can hear the Italian opera style in the arias and the overall breath) with French musical culture (Lully, court music and dances, marches) and the austerity of English theater, where there is never any complacency and everything flows in service of the drama. Through this assemblage, Purcell defined the first English Baroque style, within which Dido and Aeneas stands out as an absolute masterpiece.”

Does the vivid dynamism of the narrative influence your direction?

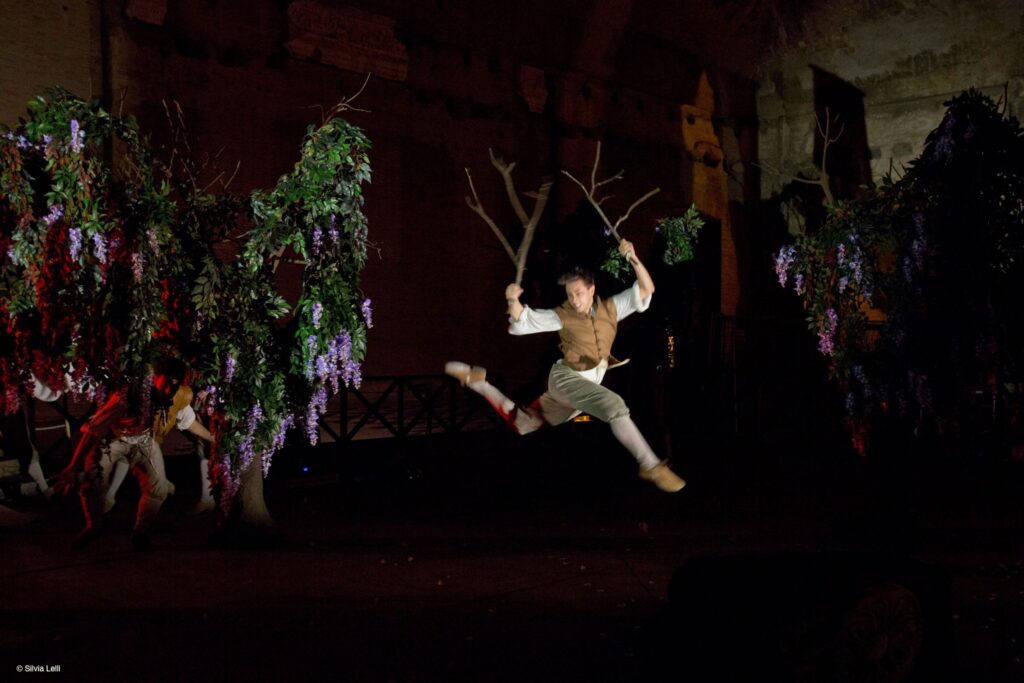

“Yes, very much. In the show, everything moves, and every change happens openly on stage. The lovers’ bed becomes the ship on which Aeneas departs, and the very boards that sealed their love transform into his condemnation. Through a group of mimes, who are somewhat like the stage servants of commedia dell’arte, objects come to life and dissolve continuously, as if shaped by the matter of dreams. In doing so, they show us how deceptive and illusory reality is. Nothing remains the same, as in life; for example, a staff can become a sword: the play is inexhaustible, like in Shakespeare’s perspective, the same that seems to have generated the witches of Dido and Aeneas. These malevolent beings burst in causing a freeze-frame each time in the accelerated flow of the action. They have the power to stop time because they reflect fate, which, weaving its web, makes time a relative notion. Amidst the total dynamism of the unfolding events, only the protagonists, as myths, remain immutable, because every myth holds symbolic values that transcend temporality. Aeneas and Dido, more than individuals, are essences: the masculine and the feminine, the reason of state and that of feelings.”

The libretto of Dido and Aeneas is inspired by the fourth canto of Virgil’s Aeneid. Does the production refer to this source?

“Unlike Purcell’s work, Virgil’s text includes Aeneas’ son, Ascanius. I stage him at the beginning as Virgil’s story requires, that is, transformed into Eros. I wanted to reintroduce him because I am convinced that this character is a decisive component of Dido’s falling in love. Seeing Aeneas as a father tenderly caring for his son deeply touches her feelings, as often happens with women, and especially with a woman longing so much for a family like Dido, who makes us understand, in the fourth book of the Aeneid, her yearning for a child by her fleeing beloved. It is Virgil himself who makes her say: ‘If only I had borne a child from you…’ In Purcell, the witches send a spirit in the guise of Mercury to Aeneas to order him to leave Carthage, making him believe it is Jupiter’s will. The false messenger in the production becomes a disguised elf. The encounter between this character, representing English theater, and Eros, emblematic of the classical world, signals the union of the two dimensions and is a way to show how, in this opera, the tradition of English theater reclaims classical culture.”